Timothy Sandefur

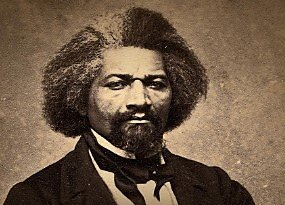

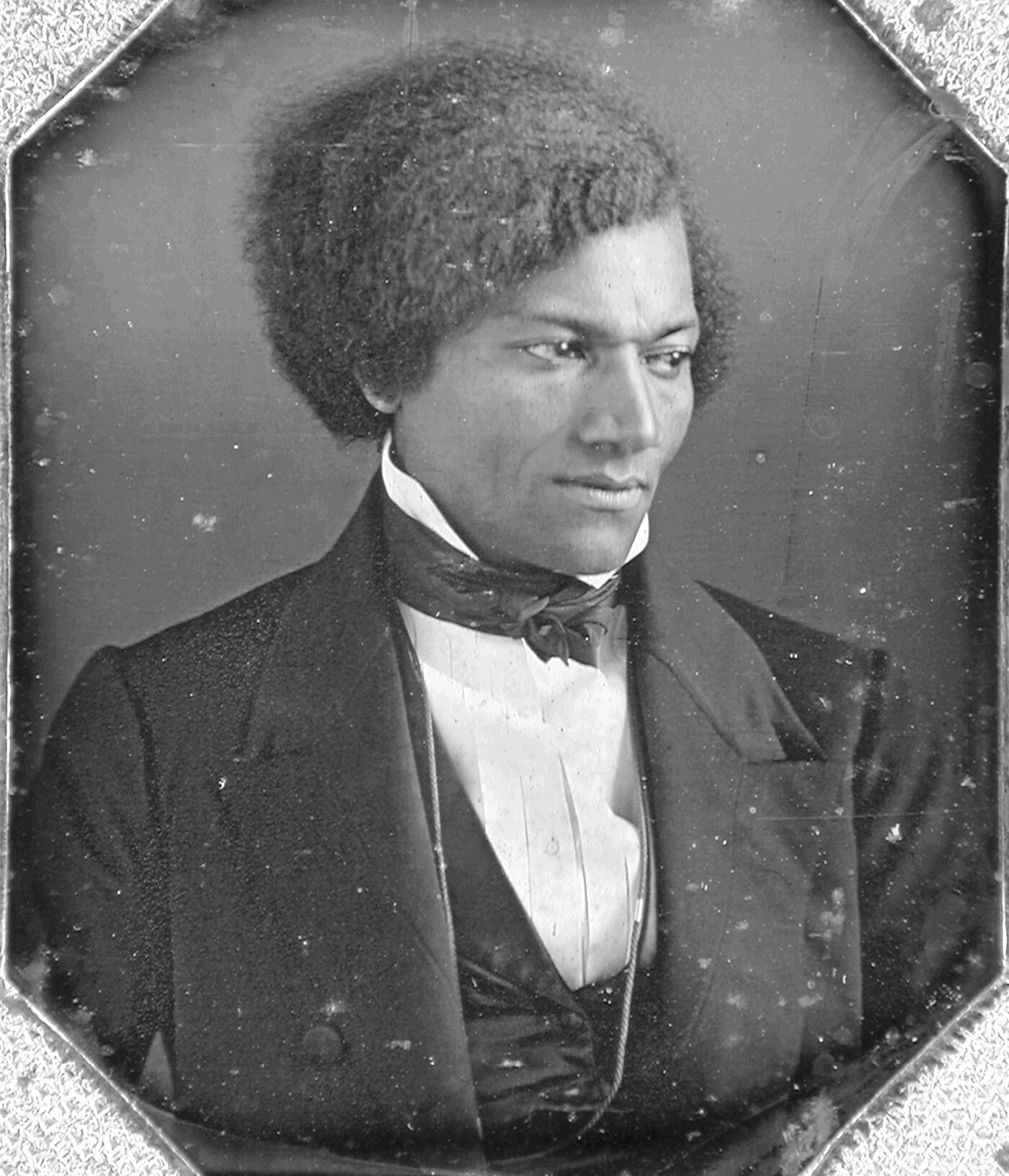

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was born enslaved in Maryland, escaped, and rose to become a journalist, author, orator, diplomat, bank president, and civil rights leader. A self-made man, he championed the Declaration of Independence’s promise that all men are born free and equal. Douglass also emphasized that black Americans must integrate into white society, a view explored by Cato Adjunct Scholar Timothy Sandefur in an excerpt below from his book, Frederick Douglass: Self-Made Man.

… Some Douglass scholars disregard critical aspects of his political views. They emphasize his belief in armed resistance to slavery but downplay his belief that the Constitution was fundamentally an anti-slavery document, or that black Americans must integrate into white society, rather than separate themselves from it.

For example, in 2009, Angela Davis—a former member of the Black Panthers and the Communist Party, and a recipient of the Soviet Union’s Lenin Peace Prize—published an edition of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass; in it, she focuses on the injustice and illegitimacy of slavery but makes no mention of Douglass’s later embrace of the Constitution and rejection of the anarchist version of abolitionism that he espoused at the time he wrote the Narrative. Her notes make no mention of Douglass’s hostility to communism, his skepticism of labor unions, his unequivocal opposition to black nationalism, or his allegiance to limited government and free enterprise. Other scholars have openly condemned Douglass for his “bourgeois” belief in “laissez-faire,” and his “blinkered” “faith in the miraculous workings of the free labor market,” and have even claimed he was “being manipulated” by the ideology of “self-possessive individualism. ”

… Opposition to slavery had been a feature of American life since the founding, but white Americans were generally stymied by the question of what to do with the slaves, once freed. Was it possible for them to remain in the United States? Thomas Jefferson, struggling with the question in his 1787 book Notes on the State of Virginia, had answered no: slaves and their descendants would never be able to forgive whites for slavery, and whites would find it impossible to let go of their racism. Freeing the slaves would therefore “produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.”

One possible solution appeared in 1816 with the formation of the American Colonization Society, which proposed to establish a colony in Africa where freed slaves could go—or perhaps be sent. Jefferson supported the society, and his friend and successor James Madison served as its president. It did manage to start a colony in Liberia, the capital of which was named Monrovia after Jefferson’s other society-supporting protégé, James Monroe. But the colonization effort was doomed from the start: over the course of its life, it arranged to move fewer than 20,000 people, compared with the total American slave population of more than 3 million. Worse, colonization was a moral outrage: most slaves had been born in America, had never visited Africa, and had no interest in going. Few had the skills needed to survive there. To deport them against their will was unconscionable—although there were plenty who wanted to try. Yet, its very futility and racism were what made colonization so attractive to many: it allowed upper-class whites to endorse anti-slavery principles, and thus appear humane, without actually taking steps to threaten the status quo. As Douglass later said, it “interpose[d] a physical impossibility between the slave and his deliverance,” making it a politically safe position for white leaders.

[William Lloyd] Garrison, more than any other figure, destroyed the respectability of the colonization movement and other moderate versions of opposing slavery. Railing against half-measures and thinly disguised racist schemes to send black Americans elsewhere, he insisted on “abolitionism” instead of colonization, which meant the immediate liberation of the slaves, without deportation, and without payment to slave owners. Masters claimed that the Constitution entitled them to be compensated if the government freed their slaves; but the new wave of abolitionists insisted that, if anyone deserved payment, it was the slaves themselves. They alone had suffered real deprivation.

Garrison’s radicalism went beyond rejecting the idea of compensated emancipation. He denounced politics in toto. The U.S. Constitution was literally a deal with the devil, he said, because it protected slavery—and he burned it on stage during his speeches.

…. In fact, as late as the end of 1862, Lincoln was still considering, apparently with all seriousness, the possibility of colonizing freed slaves to Africa. He told a delegation of black leaders in an August meeting that they should take advantage of a congressional proposal to establish a colony there and, in December, proposed in his annual message to Congress that the Constitution be amended to provide for colonization. This was anathema to Douglass but not to all black leaders. Toward the end of the war, Lincoln even met warmly with Martin Delany, who had once been Douglass’s coeditor on The North Star before the two split over Delany’s support for colonization. Lincoln appointed Delany a major in the Army, and although he promised Douglass a similar appointment, that never came about. Douglass was infuriated by the talk of colonization—“ten thousand times refuted,” in his view. “What shall be done with the four million slaves if they are emancipated? ” he wrote.

Our answer is, do nothing with them; mind your business, and let them mind theirs. Your doing with them is their greatest misfortune. They have been undone by your doings, and all they now ask, and really have need of at your hands, is just to let them alone.… As colored men, we only ask to be allowed to do with ourselves.… Let us stand upon our own legs, work with our own hands, and eat bread in the sweat of our own brows.

The Administration’s talk of colonization petered out at the beginning of 1863, when Lincoln followed through on his promise to proclaim the slaves in the rebel states “forever free. ”

… Douglass was equally frustrated to find that some people were yet again reviving the old prewar canard of African colonization, including some black leaders. “All this native land talk is nonsense,” Douglass roared. “The native land of the American negro is America. His bones, his muscles, his sinews, are all American. His ancestors for two hundred and seventy years have lived, and labored, and died on American soil, and millions of his posterity have inherited Caucasian blood.” Worse, the colonization idea tended “to throw over the negro a mantle of despair” and encouraged whites to ratchet up the persecution in hopes that blacks might leave the country.

Colonization was merely an evasion of responsibility for fixing the problem of racial oppression. The only real answer was for white Americans to abandon their prejudices, “cultivate kindness and humanity,” and give effect to the Constitution and the demands of justice. Invoking the Declaration of Independence, Douglass sounded once more his lifelong theme:

I would call to mind the sublime and glorious truths with which, at its birth, [the United States] saluted a listening world. Its voice then, was the trump of an archangel, summoning hoary forms of oppression and time honored tyranny, to judgment. Crowned heads heard it and shrieked. Toiling millions heard it and clapped their hands for joy. It announced the advent of a nation, based upon human brotherhood and the self-evident truths of liberty and equality. Its mission was the redemption of the world from the bondage of ages. Apply these sublime and glorious truths to the situation now before you. Put away your race prejudice. Banish the idea that one class must rule over another. Recognize the fact that the rights of the humblest citizen are as worthy of protection as are those of the highest, and your problem will be solved … [and] your Republic will stand and flourish forever.

Eight days after this lecture, 24-year-old John Buckner, accused of raping a white woman in St. Louis, was snatched from his parents’ home and hanged on a bridge over the Meramec River in front of 100 witnesses. The coroner called it suicide.

…. He [Douglass] was an authentic genius, who through his own effort became the nation’s foremost abolitionist, with the sole exception of William Lloyd Garrison. Yet he transcended Garrison. More than an orator, he was a scholar and an intellectual who went beyond mere “agitation.” He delved into some of the most complicated legal issues of his day and articulated a principled defense of classical liberalism and individual rights for all Americans. Of the pro-Constitution abolitionists, he was by far the most effective, devoting his postwar career to realizing the principles of the Declaration of Independence for the freedmen and their descendants. As Douglass scholar Peter Myers concludes, he “produced the most powerful argument for the affirmation of those principles in the history of African American political thought. ”

Douglass was the foremost opponent of the colonization schemes that were offered time and again by both black and white Americans in his day—people who, in his view, were ultimately ignoring the moral imperative of the U.S. Constitution. Separatism, he believed, was an evasion of, not a solution to, injustice—and civic engagement was more important than maintaining one’s own moral sanctity. His unique contribution to American political philosophy is well summarized in the contrast between the mottos he and Garrison used for their newspapers. Instead of Garrison’s call for separation, “no union with slaveholders,” Douglass demanded equality: “All rights for all. ”

…. He believed above all else in the potential of the free individual. Within each of us is a sacred personal uniqueness, one that can and will take responsibility for building a noble and beautiful future, if only our hands are untied. And he believed that the U.S. Constitution protected that freedom—which was why it deserved to be cherished and defended. A self-made man himself, he viewed America as a land of self-made people: a place where every person, white or black, male or female, had the right, and would someday have the freedom, to pursue life as he or she chose. “We have as a people no past and very little present, but a boundless and glorious future,” he said in his “Self-Made Men” lecture.

To order a copy of Frederick Douglass: Self-Made Man, click here.