Matthew Cavedon

The past couple of months (for that matter, perhaps any couple of months) have served up story after story about what can go wrong when society offers criminals mercy and redemption. Most infamously, millions of people have seen the video of Decarlos Brown Jr. stabbing Ukrainian refugee Iryna Zarutska to death on a Charlotte train. People like Brown—who had 14 prior arrests and had been to prison for armed robbery—are the obvious case for harsh responses to crime. That’s why President Trump and others have pointed straight at him in arguing for high barriers to bail and increasing the use of the death penalty.

Society does need to take the danger posed by people like Brown seriously, but his stories are easy to see. When someone acts violently after being released on bail or following their completion of a criminal sentence, they often make the headlines, and so does their criminal history. It’s easy to see an alternative universe in which they weren’t on the streets to strike again.

It’s harder to see what happens when someone doesn’t reoffend. For every person like Brown, there are criminals who change their lives. Their stories rarely go viral, but what they’re doing in our collective blind spots matters, too. That’s why I’ve been trying hard to see invisible people, and I think that’s the key to understanding the case for criminal justice reform.

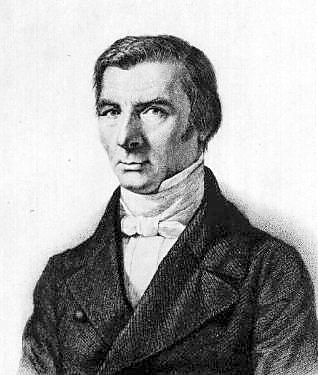

Humanity’s biases against what is unseen once caught the attention of the French economist Frédéric Bastiat. He noted that every action, and every law, sets off a series of effects—only some of which can be readily seen. As for the rest, “we are lucky if we foresee them,” Bastiat cautions. We often fall into the trap of picking a small seen benefit over a larger unseen one, especially if the second option involves risk that can be readily understood.

That temptation is especially present in conversations about criminal justice. We see what happens when someone gets out and then does more wrong. At this point, though, like Bastiat, “I am obliged to cry: ‘Stop!’ Your theory has stopped at what is seen and takes no account of what is not seen.”

What is almost never seen is what liberty, in the form of release on bail or a shorter prison sentence, can actually mean. Think of just one person who succeeds in becoming a responsible member of society. Considered by herself, that one person can return to the community as a daughter able to help her aging parents and neighbors, an employee who fills a job vacancy, a recovered addict who can mentor others along the way to sobriety, or a parent who provides and cares for her children. In other words, this is a person with a future, even of ordinary contributions—instead of remaining yet another inmate who is warehoused, fed, and confined 24/7 at taxpayer expense.

A person like the woman I just described rarely makes it onto the news. But we know they are out there, because they show up in statistics.

A comparative study of 33 cities by the Brennan Center for Justice “found no statistically significant relationship between bail reforms and trends in crime generally or violent crime specifically.” Put simply, reducing the number of people awaiting trial in jail need not mean more theft—even as doing so means more opportunities for offenders to change for the better. Indeed, another study, by the Data Collaborative for Justice, “found that cashless bail for misdemeanors and non-violent felonies in New York cut the likelihood that a person would be rearrested for another crime by about 12 percent.”

Public conversation inevitably focuses on the Decarlos Browns—not these people, quietly changing their lives. Discussing the statistics (which align with findings from other studies as well), indigent defense advocate Scott Hechinger echoed Bastiat’s point perfectly: “We have hundreds of thousands of success stories … probably millions of people who have been released pre-trial, show back up to court, being in their jobs, [who] are able to be with their families [and] pay their bills….” But they’re the invisible people.

Pretrial release is not the only setting where hope matters. The US Department of Justice keeps track of how many former state prisoners reoffend after their release. The records don’t paint an overly rosy picture. Faced with the challenges of bad habits (some learned or worsened in prison), social circles that may encourage more offenses rather than rehabilitation, and the economic hardships that society imposes on convicts, many newly freed people turn back to crime. Most released state prisoners are rearrested at some point in their first decade back in the community.

In spite of these difficulties, fewer than half of former state inmates return to prison within five years, nearly 60 percent of men violent offenders are not reincarcerated, and two-thirds of women convicts avoid reimprisonment. Hundreds of thousands of people are making enough improvement not to be sent back, despite being watched closely by police, probation, parole, and judges.

Good perspective in criminal justice means seeing both the seen and the unseen. I’m not a prison abolitionist. There are dangerous people in this world who need to be removed from society, at least for a time. It’s right to ask what Brown was doing on a Charlotte train.

But we need to look with both eyes open. It’s too easy to overlook the unseen costs of detention and incarceration: disrupted families and neighborhoods, workplaces, and churches.

Crime threatens to cause these. So do short-sighted responses to it.